A Flood of Iranian Propaganda on Wikipedia is Reshaping the Protest Narrative

Thousands of videos and images from Iranian state media are being mass uploaded to one of the world’s most trusted knowledge platforms

As Iran’s regime carried out what observers have described as one of the bloodiest two-day massacres in modern history — with estimates suggesting as many as 36,500 people killed — the government simultaneously shut down internet access, blocked journalists, and sealed the country off from outside reporting.

Now an NPOV investigation reveals a surge of protest-related media sourced from Iranian state outlets appearing on Wikimedia Commons, Wikipedia’s media repository.

In recent weeks, over 10,000 images and videos from Iranian state-owned or controlled media outlets—most related to the recent protests—have been uploaded to Wikimedia Commons. The content appears as the results for searches on “Iran protests,” “Iran protests 2026,” “Khamenei,” and related keywords.

Out of thousands of pieces of content returned on these searches, only a few dozen—mostly of an anti-regime protest in Sweden—were not sourced from Iranian state media. Pro-regime content continued to be uploaded in real time during NPOV’s investigation—with hundreds more added during the course of our investigation.

Sanctioned State Media in Wikipedia’s Media Pipeline

The Iranian-sourced images and videos are produced and licensed by three Iranian government media outlets: Khamenei.ir, the official website of Iran’s Supreme Leader; Mehr News Agency, owned by Iranian government’s Islamic Ideology Dissemination Organization; and Tasnim News Agency, an entity sanctioned by the U.S. government on account of its ownership by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, a U.S.-designated Foreign Terror Organization.

The presence of this content on Wikimedia Commons, which, along with Wikipedia, is owned and operated by Wikimedia Foundation, a U.S.-based nonprofit, raises potential sanctions-compliance and liability questions.

Clicking on the attribution section on the Wikimedia Commons files leads users directly to the Iranian state propaganda outlets’ website. This includes Khamenei.ir, where the footer notes that the site is The Official Website of the Office for the Preservation and Publication of the Works of the Grand Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Khamenei.

Nearly all of the content has been uploaded by a single user, 999real, an account with less than 1,000 edits on Wikipedia, but over 1 million edits on Wikimedia Commons.

999real is the third-ranked author on the Wikipedia entry for the Tasnim News Agency. This is despite the fact that the account was registered less than three years ago, in November 2023. (By comparison, the first- and second-ranked authors on the Tasnim entry were registered 20 and 17 years ago, respectively.)

It’s unclear whether 999real’s mass upload of Iranian state-affiliated media is coordinated by Tehran. What is clear is that the content of the images and videos distinctly present the viewpoint pushed by the government. The titles and content provide strong indication that these are narrative artifacts designed to depict protesters as violent extremists while portraying regime gatherings as expressions of national unity.

Reshaping the Narrative Through High-Impact Video

The first video in the results returned for “Iran protest 2026” is titled Memorable moments of Iranian people’s tremendous participation in rallies in Tehran. The video, which bears the Khamenei.ir watermark, begins with a man shouting over a loudspeaker “Marg bar Āmrikā”—death to America. A crowd responds with the same chant. The video cuts to a man holding a sign that reads “DOWN WITH ISRAEL.” Seconds later the video shows a crowd chanting “Khamenei, I respond to your call.”

Another top video result is titled Exclusive interview conducted by Khamenei.ir World Service. It, too, carries the Khamenei.ir watermark. The video begins with an Iranian state media figure stopping people at a pro-regime protest to ask them questions on camera. A young woman in a chador and wrapped in the Islamic Republic of Iran flag tells the camera, “We came to say that it’s not our country that’s coming to an end. It’s the devil’s time that’s running out.”

In the video, another woman, holding a picture of the Supreme Leader, says, “We came here today for our martyrs, for Ayatollah Khamenei, for Iran.” Interviewees are given a small grey box with a zip carrying a fake press pass that reads:

Congratulations, you’re now a Western media journalist. For your first report on Iranian youth prepare an interview so the world understands the following. Point one: Iranian youth are politically dependent on the West. Second point: Iranian youth have turned their backs on religion. Third point: Iranian youth are morally corrupt.

Interviewees react with disgust or ridicule. As the music swells into an orchestral cinematic score, the video closes with a speech by Khamenei about “brave Iranian youth” and their struggle against the enemy.

In these two instances, and dozens others like them, the Wikimedia Commons files include licensing and attribution details that take users to the official website of the Supreme Leader, or the regime media outlets listed as the source.

The videos are narrative artifacts designed to depict protesters as violent extremists while portraying regime gatherings as expressions of national unity

Other video titles include The Iranian nation is strong, powerful and aware and Confessions of an armed rioter arrested in Khorramabad protests. Several clips embed direct statements from Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, including a January 12, 2026 address warning “traitorous hirelings” and praising pro-regime rallies. In addition to Khamenei.ir, Mehr and Tasnim repeatedly appear as credited sources.

Once on Wikimedia Commons, this content becomes available to Wikipedia articles across hundreds of languages. NPOV queried ChatGPT asking where users might find videos from the 2026 Iran protests. The first suggestion provided is to search for videos on Wikimedia Commons.

Martyrs, Mosques, and the Visual Language of Retaliation

In the Tasnim News report, People’s Reaction to Trump’s Renewed Support for Armed Rioters, the visual language shifts to the iconography of state martyrdom. Filmed during the funeral for security personnel on January 14, 2026, the video is saturated with the imagery of the Islamic Republic flag draped over coffins.

The soundscape is dominated by Shiite mourning chants—and the rhythmic thud of chest-beating. Amidst this sea of green, white, and red flags, the camera focuses on women in full black chadors weeping for “security martyrs.” One woman clutches a portrait of the Supreme Leader and shouts a direct rebuttal to the American president:

“Trump thinks he can break us with his tweets? These are our sons! We will never let the rioters take our streets!”

Central to the state’s January 2026 media strategy was the constant circulation of imagery showing burned-out mosques and charred Qurans. Included in the uploaded repository are clips featuring high-definition footage of the Abuzar Mosque in Tehran (notably the site of a 1981 assassination attempt on Khamenei) showing gutted interiors and smoke-damaged prayer rugs.

Imagery of “rioters” attacking religious sanctities has been used to mobilize the government’s religious base and to justify the “Red Line” policy declared by the Revolutionary Guards on January 10.

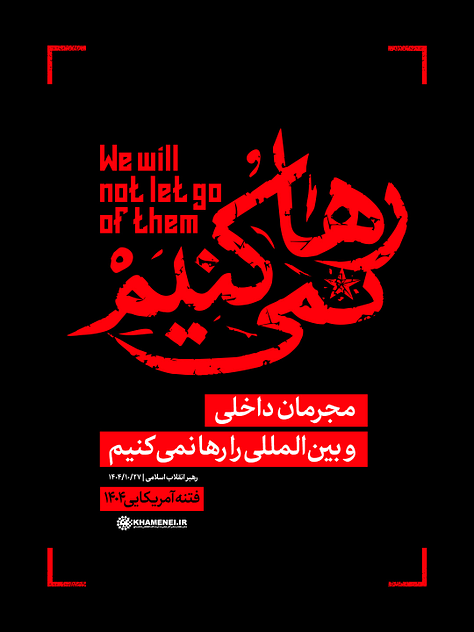

Filtering for images on Wikimedia Commons brings up dozens of the images stamped with distinctive red corner brackets and HUD-like overlays alongside organizational branding, also in red, from Tasnim News Agency and Khamenei.ir. On Wikimedia Commons, the files are identified as part of a collection labelled “We will not let go of them.”

Targeting Trump: Direct Threat Imagery

In several of these assets, English-language messaging appears within the same graphic package, including the headline “We will not let go of them.” The phrase is a reference to a January 17 speech given by Khamenei, where he said:

We will not lead the country into war, but we will not let go of the domestic criminals and—more importantly—the international criminals.

Khamenei referred to Trump in that speech as a “criminal” and blamed the American president for the “casualties and damage” caused by the protests.

Several Commons images also contain direct references to Trump. Multiple crowd photographs show demonstrators holding professionally printed posters of Trump with a bloody handprint across his cheek—an apparent threat aimed at the U.S. president. The presence of Tasnim branding on these posters indicates they originated from Iranian state media before being uploaded to Wikimedia Commons.

999real is not the first account to do mass uploads of Iran state-media-sourced content to Wiki Commons. In 2017, an account named Mbarzi uploaded hundreds such images. Mbarzi—whose User page features a shining gif of an Arabic caligraphy of the Quranic invocation “In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful”—is the top editor on the entry for IRIB Ofogh, a channel on the Iranian state-controlled TV network Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting.

Another user who engaged in the same pattern of mass uploading Iran state media content was subsequently banned for operating a number of sock accounts. The user admitted to being Iranian but did not admit to overt government coordination.

This is not isolated misuse of an open platform. It is large-scale ingestion of Iranian state-produced media into Wikimedia Commons—and by extension Wikipedia itself—at the precise moment the government was violently suppressing dissent at home.

While journalists are blocked and internet access is restricted inside Iran, professionally produced content from Khamenei.ir, Tasnim, and Mehr is being uploaded into one of the world’s most trusted knowledge infrastructures, licensed for global reuse and embedded into reference systems relied upon by millions.

Whether these uploads are coordinated by Iranian authorities or carried out by third parties sourcing directly from state outlets remains unclear. What is clear is that sanctioned and state-affiliated media has been systematically introduced into Wikipedia’s media pipeline at scale, shaping how the 2026 unrest appears to the outside world. The material remains live. The uploads continue. And the historical record of the crackdown is being re-constructed—raising urgent questions about platform governance, sanctions exposure, and how open information systems can be leveraged during moments of mass violence.

Editor’s Note: NPOV is bringing influence operations online to light. We rely on reader subscriptions to help us continue this work. Please consider a paid subscription or sharing this investigation.