Why Grokipedia May Actually be the Wikipedia-Killer Elon Musk Promised

The age of the AI encyclopedia has officially begun.

For the past 20 years, Wikipedia has dominated the online encyclopedia market. While a number of other competitors have sprung up, none has even come close to challenging the world’s first crowdsourced online encyclopedia. This knowledge monopoly shaped the internet in its most formative years, creating a framework for online information dominated by a single worldview.

All that changed last week when Elon Musk rolled out Grokipedia, xAI’s online encyclopedia. He hasn’t said how many people are using it, but true to Musk’s epic -trolling fashion, it was launched the same day that Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales’ book was published. On X, much of the discourse about Grokipedia has focused on how different the content of various flashpoint entries is in each encyclopedia, including the Covid-19 lab leak theory, President Donald Trump, and Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

This divergence is indeed significant. Take lab leak. For years, Wikipedia “informed” the world that the idea that the Covid virus originated in a laboratory is a conspiracy theory unsupported by science. As a reporter who investigated this topic extensively, I can tell you this idea is so wildly inaccurate that I can’t make sense of it except as deliberate falsehood. Grokipedia, on the other hand, offers a clear-eyed assessment of how the conspiracy theory narrative was seeded into the discourse—and, importantly, by whom. Grokipedia’s first citation is an unclassified intelligence overview from the director of national intelligence.

No doubt, there are countless other examples we could find in this same vein. Conversely, there are probably numerous cases where Wikipedia’s take on a topic does a better job than its newest competitor. But what’s important to understand is that this isn’t just about the encyclopedia wars. Rather, the arrival of Grokipedia signals a shift in not just how information is distributed, but what counts as information at all.

When Wikipedia was launched in 2001, probably the single most important factor in spurring its growth was its crowdsourced nature. Before the launch of Wikipedia, Larry Sanger, one of Jimmy Wales’ employees at his early-internet company, Bomis, was busy building the digital version of Encyclopedia Britannica. The idea behind Nupedia, as the project was called, was that topics would go through a fairly rigorous editorial process before getting to that final state of publication.

This was as slow and expensive as it sounds. When Sanger hit on the idea of marrying the concept of an online encyclopedia with a “wiki,” a web page that could be edited by anyone, Wikipedia was born. Wikipedia’s growth had that kind of wildfire effect that signals an online network is racing toward critical mass. And it was.

But, just as importantly, Wikipedia had an irresistible story to tell—and, in Wales, a skilled storyteller. This was the kind of idea the media adores. It was completely original, yet a twist on an old tradition. It spoke to one of the media’s favorite feel-good messages—neutrality—but layered on a new story about democratized knowledge. Most importantly, the site’s rate of growth was vertical. For all these reasons, Wikipedia became not just the first but the only online encyclopedia that mattered.

The problem with monopolies is that they fail not because a well-funded competitor starts doing the same thing, better. They fail because an upstart does it differently. But on the road to wrack and ruin, monopolies tend to become functionally irrelevant. No one growing up in the 1980s (or earlier) could have imagined life without Kodak. “Kodak moments” was such a powerful marketing campaign because it reflected reality deeply. We lived for those moments and, no matter how fleeting, Kodak made them seem eternal.

Wikipedia did something similar, providing early internet users with a solution to a problem we never knew we had: We had to look stuff up. Constantly. And with just a few keystrokes in Google, we had our answer to almost anything. This de facto partnership with Google, which cannily monetized Wikipedia’s free content to the tune of tens of billions of dollars in ad revenue, made Wikipedia’s dominance an entrenched feature of the internet.

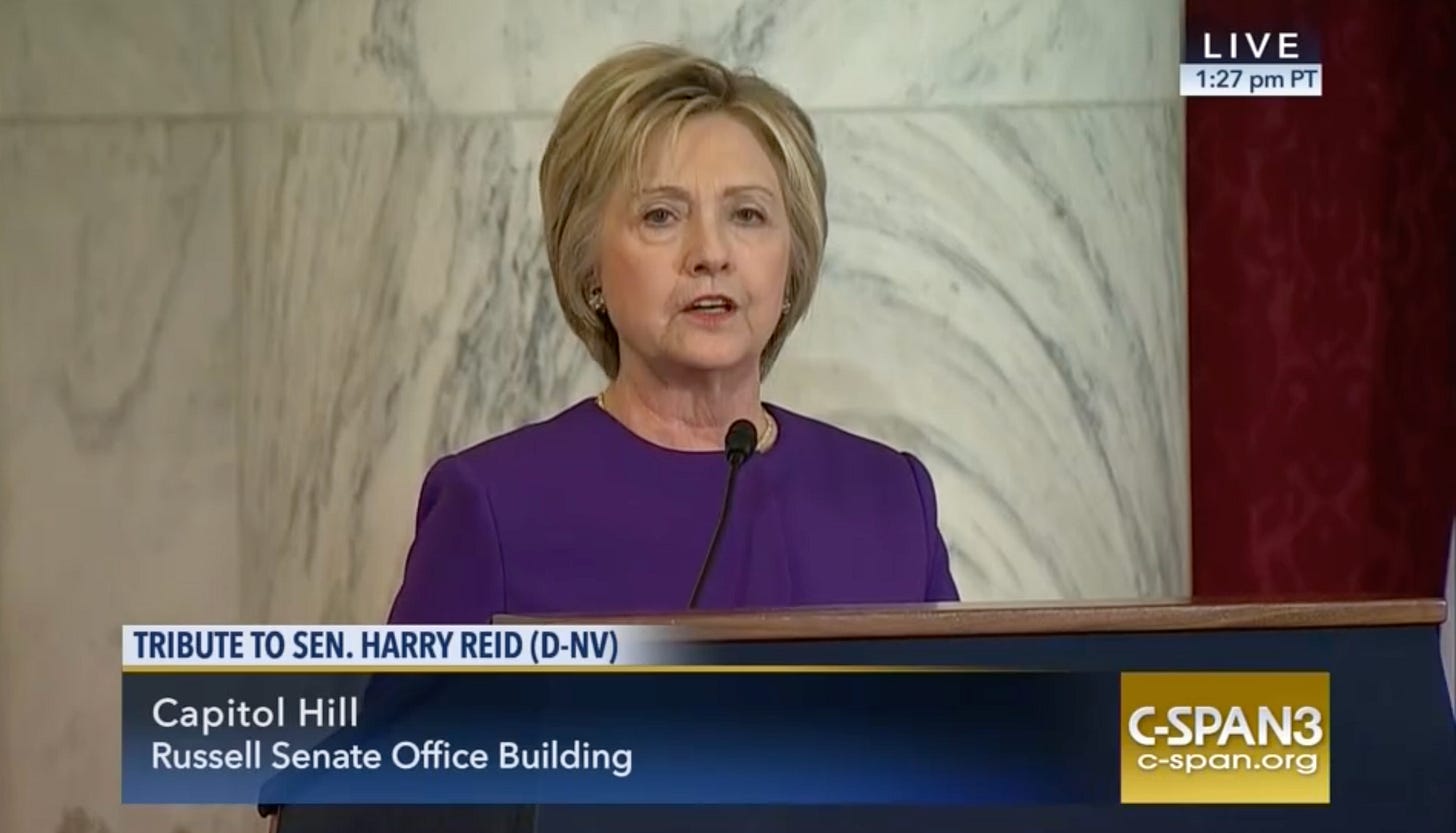

By 2017, Wikipedia had become “global knowledge infrastructure,” as it is described by Wikimedia Foundation, the U.S.-based nongovernmental organization that owns and oversees the website. Wikipedia was the piping that funneled news reporting from “Reliable sources,” which Wikipedia depends on to make and support claims, into the wider internet. In the wake of the “fake news epidemic” declared by Hillary Clinton in December 2016, Wikipedia became the world’s repository for ground truth—one that misinformation could be measured against on thousands of topics.

But with the epistemological earthquake following Covid, the Black Lives Matter riots, and Russiagate, people began to realize that, on Wikipedia too, not everything is what it seems. The site’s story about neutral, crowdsourced information was slowly revealed to be a kind of myth.

Far from the 200,000 editors who, Wikipedia claims, produce the site’s entries, the majority of content is created by a few thousand power users. There are probably no more than 600 or 700 active admins who determine which view on a contentious claim wins out. And, as Sanger pointed out in his Nine Theses on Wikipedia, which he nailed to Wikipedia’s proverbial door in late September, only 62 super- users govern the site’s most important functions—including the equivalent of its high court, which adjudicates major disputes, and its internal police force, which wields the power to investigate and ban users.

Most importantly, for all its talk about an “air gap” between Wikipedia and the Wikimedia Foundation, the parent organization reserves the right—and bears the power—to ban any user, and revert any edit, without so much as disclosing the evidence or reasoning behind the decision.

This all may sound vaguely familiar. One of Wikipedia’s greatest illusions is that it is primarily an encyclopedia. In reality, it’s a social media site. Its posts are called “entries,” and its users are “editors.” But if you peel away the sleek interface, what you find is X, only with a lower posting frequency and more rules. The fundamental dynamics—ideological battling, rampant harassment, memetic jargon, clout accumulation, and the unseen, omnipotent God-user in the form of the site’s owner-operator—are the same.

Enter Grokipedia. While we’ve all been busy scoring virality points by comparing articles from the two encyclopedias on X, one of the biggest points of differentiation has escaped us: On Grokipedia, there are no editors. This is the core departure Grokipedia makes not just from Wikipedia but from the entire tradition of the encyclopedia as we’ve understood it for centuries.

With the epistemological earthquake following Covid, the BLM riots, and Russiagate, people began to realize that, on Wikipedia too, not everything is what it seems.

Grokipedia is, instead, the world’s first AI encyclopedia. In true Muskian fashion, the name of the site reflects this strangeness. The word grok comes from Robert Heinlein’s 1961 novel, Stranger in a Strange Land, where it somewhat literally means “to drink” but functionally means “to understand,” the way “I see” means the same thing to us. (H/t Wikipedia.) Today, to “grok” something means to understand it intuitively, at a gut level—the way the human body absorbs and integrates water.

Which is all very involved, very strange, and very Musk. But like all things Elon, it also cannot be ignored or dismissed. Musk, the founder and CEO of xAI, has said that Grokipedia is already 10 times better than Wikipedia, and that version 1.0 (the launch version is 0.1) will be 10 times better than this one. That may or may not be true. But if one thing is certain, it’s that no matter how bold or even audacious the claim, Elon Musk delivers. It may not be precisely on schedule, or exactly the way we imagined, but from Tesla to SpaceX to Neuralink to X, whatever it is shifts the paradigm of an industry—and sometimes much more.

At a very minimum, the significance of Grokipedia is that it has killed Wikipedia. It’s not that Wikipedia will suddenly cease to exist, that frontier AI models will stop training on its data, or that Google will stop pulling its content into virtually every topic search online. All that will continue for some time. Rather, Grokipedia has overwritten Wikipedia’s most valuable asset—its story—which now feels dated, the information equivalent of Obama’s famous tan suit: exciting, daring, new, suggestive—at the time. But, in retrospect, it’s a shrug of the cultural shoulders.

This is the reality of our world today: It’s not so much about the information—but the storytelling surrounding the information. The media was all-knowing until it wasn’t. Twitter was a gift from the gods of journalism until it became a curse. Facebook was connecting the world before it backslid into a sprawling dump where Boomers sip conspiracy theories. Wikipedia was crowdsourced, neutral knowledge—a shiny new object of cosmic significance. Now it’s encyclopedia Bluesky.

Grokipedia 1.0 may very well be 10 times greater than its incipient version and 100 times better than Wikipedia. Either way, the world now has its first—but certainly not its last—AI encyclopedia. Whether that’s a good or bad thing (or both, in various doses) remains to be seen. What is clear is that one hell of a story is about to be told.

Editor’s note: NPOV is launching a new Wikipedia investigation later this month on a topic of geopolitical important. Subscribe today, if you haven’t already, and please share our content with one or two people who will appreciate learning more about Wikipedia’s outsize role in our information ecosystem.

You can suggest an edit on Grokipedia and the the AI will decide to change it or not. Look up the controversial subjects like “gender” and you can already see the activists trying to correct the article. But grok says no.

Wikipedia became a monopolist, of the kind people used to be concerned about in newspaper ownership or desktop computing. Yet Western governments have never attempted to break up its monopoly: why is that?